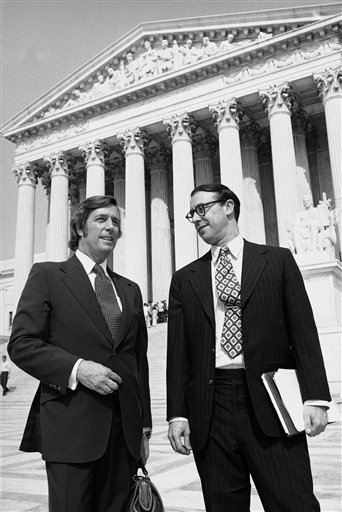

The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press (RCFP) has played an important role in most of the controversies over press freedom and freedom of information since its founding in 1970. The RCFP gained a reputation for agressive advocacy under director Jack Landau, who advocated "guerilla warfare" by reporters in defense of their First Amendment rights if more polite methods failed. Here, Landau, right, chats with lawyer E. Barrett Prettyman after Prettyman argued that judges are subjecting the press to "flagrantly unconstitutional" gag orders during an appearance before the the Supreme Court in 1976. (AP Photo/Harvey Georges, used with permission from the Associated Press)

The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press (RCFP) has played an important role in most of the controversies over press freedom and freedom of information since its founding in 1970.

A group of journalists — among them Ben Bradlee of the Washington Post, Fred Graham, then with the New York Times, and Jack Nelson of the Los Angeles Times — launched the committee in response to a wave of government subpoenas ordering journalists to reveal confidential sources. Publishers and editors usually fought the subpoenas, but the founding members of the reporters committee believed that an organization was needed to represent their sometimes divergent interests.

Based in Washington, D.C., and operating on a shoestring budget, the committee was quickly drawn into a number of controversies.

After the Supreme Court ruled in Branzburg v. Hayes (1972) that the First Amendment does not give reporters the right to refuse to reveal their sources, the committee fought unsuccessfully for passage of a federal shield law to protect reporters from having to do so. The committee was more successful in challenging a plan that would have given President Richard M. Nixon control over his presidential papers following his resignation in 1974.

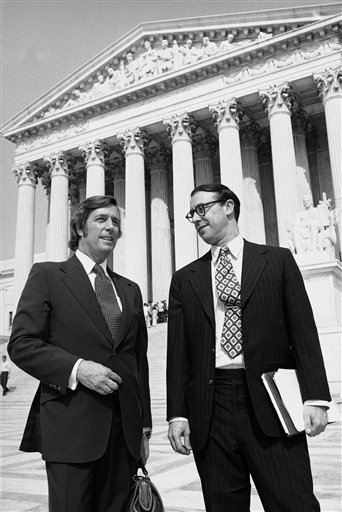

The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press fought unsuccessfully for passage of a federal shield law to protect reporters from having to reveal their sources. In this photo, Lucy Dalglish, Executive Director of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, left, talks with Susan Burgess, center, and Kirsten Mitchell, right, at their office in Arlington, Virginia, in this 2006 photo. (AP Photo/Lauren Victoria Burke, with permission from the Associated Press)

The committee gained a reputation for absolutist, aggressive advocacy under director Jack Landau, who advocated “guerrilla warfare” by reporters in defense of their First Amendment rights if more polite methods failed.

That advocacy included litigation in the name of the committee itself, leading to two Supreme Court rulings, both of which it lost. In the first, Kissinger v. Reporters Committee (1980), the Court rejected requests by the committee and several journalists for notes and records of former secretary of state Henry Kissinger.

The second decision, U.S. Department of Justice v. Reporters Committee (1989), began with a request from the committee and CBS News in 1978 for access to the FBI “rap sheet” on an organized crime figure. The Court ruled that the FBI could withhold such information under a provision of the Freedom of Information Act protecting against invasion of personal privacy.

When American reporters were barred from covering the U.S. invasion of Grenada in 1983, Landau advocated suing the Reagan administration based in part on an asserted First Amendment right of access to combat. This position was viewed as extreme even by other journalists and was one of the factors that led to his departure the following year.

Subsequent directors Jane Kirtley and Lucy Dalglish changed the tone of the committee, while remaining forceful advocates for journalists. The committee stepped back from being a direct litigant, instead filing amicus briefs on behalf of journalists and news organizations. The committee provides free legal assistance to journalists who face legal obstacles in their pursuit of the news.

Following the al-Qaida attacks of September 11, 2001, the committee monitored and publicized various government restrictions on the free flow of information. Returning to its roots, the committee in recent years has also battled a new wave of subpoenas asking journalists to reveal confidential sources.

The RCFP publishes The Open Government Guide, described as a “complete compendium on every state’s open records and open meetings laws.” The publication is also accessible at the group’s website. Since the Trump administration began in 2017, more threats against the news media challenged the committee in many ways. The committee increased its staff and became a leader in direct litigation on behalf of the media and in providing legal services and hotlines for a range of new media and news organizations.

Washington D.C.-based attorney Bruce D. Brown succeeded Dalglish as the group’s executive director in 2012. The Reporters Committee remains very active in filing amicus briefs in many First Amendment cases.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in 2017. Tony Mauro covered the U.S. Supreme Court for more than 40 years for several publications before being semi-retired in 2019. He served on the steering committee of The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press for 36 years, and was inducted into the Freedom of Information Hall of Fame for his advocacy for greater transparency in the federal courts.